A brief note to those in Florida, I hope Hurricane Milton has not impacted you too terribly and that we can get back to “normal” soon. Sending love.

I always assumed that dabbling would be my downfall. That flânerie is my fatal flaw. It’s why, with mixed feelings, I chose “dilettante” as one of my eight personal archetypes while reading Sacred Contracts.

All these terms come with an air of judgment—someone who dabbles can’t pick a lane. A flâneur is a privileged observer, never engaging first-hand with society. The dilettante is an amateur, supporting the arts and partaking in casual hobbies but never fully committing himself to mastery.

Some might say the dabbler never gets his hands dirty—never commits to a discipline, with the risk that he might be terrible at it.

All my life, I’ve jumped around. What can I say, I have a fear of missing out. I get frustrated with bureaucracy, politics, and the soul-crushing demands of free market capitalism—which is designed for laborers to specialize in order to succeed. To know something deeply is to be an expert and thus, valuable to a market.

It’s the efficient thing to do, and it’s why nowadays our entire system is designed to categorize and label young people early on, so that they can follow prescripted educational paths and enter the workforce as trained specialists in say, radiology or mechanical engineering or graphic design.

But lately I’ve wondered…how will artificial intelligence (AI) change what’s deemed valuable as human labor? As large language models (LLMs) grow exponentially more sophisticated, which human skills will be in-demand? If computers begin to do many things as well as or better than humans can, where does that leave us?

I predict that generalists, not specialists, will rule the future human labor market. Robots, computers, and algorithms will take the place of subject matter specialists and some function-specific production staff. What will matter is knowing how to wield these tools effectively, knowing when original human creativity is necessary and when it’s not. Curiosity and novel, intuitive thinking, both typical strengths of generalists, may become the most crucial skills of all. The ability to draw broad connections between disciplines and silos of knowledge may be humans’ only place in an AI-dominated world—one where generalists already succeed.

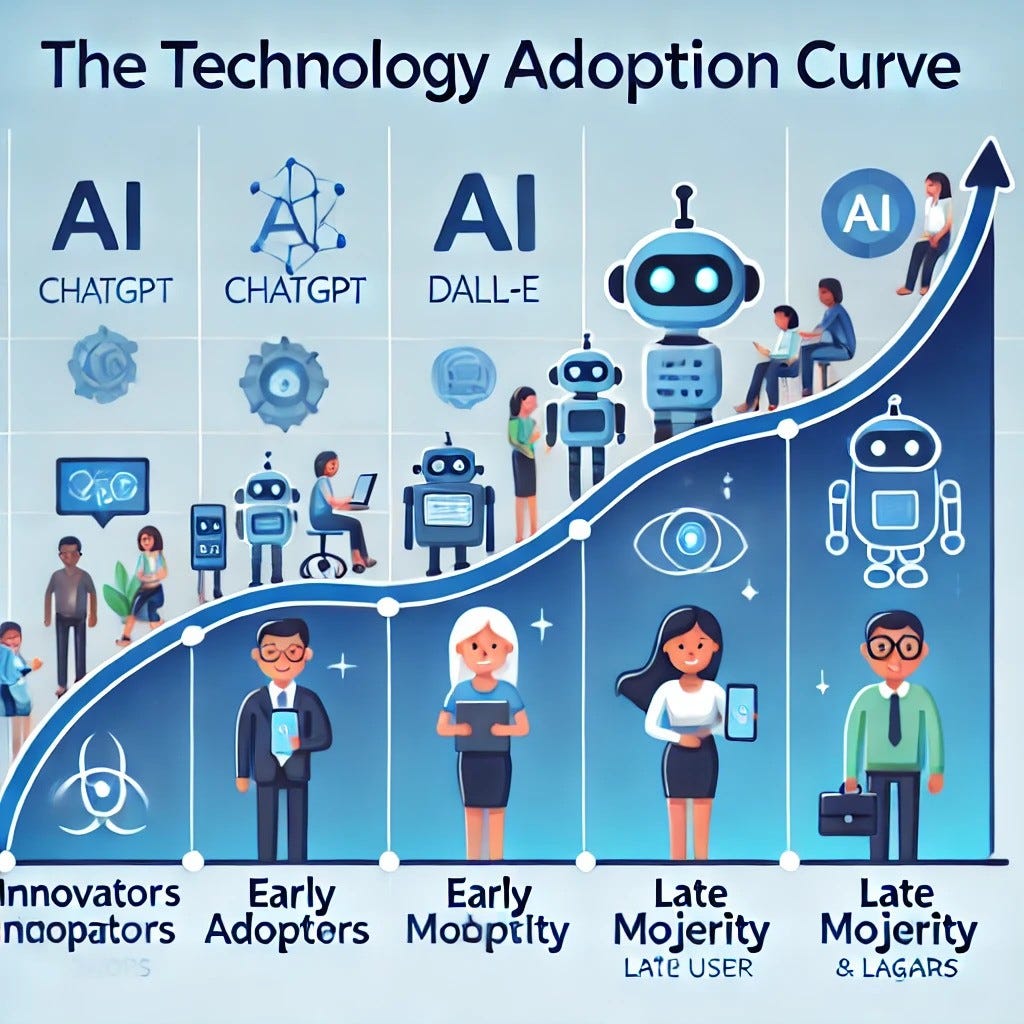

I think it’s hard to imagine what ten or twenty years from now will look like, because we’ve only just begun to scratch the surface of what’s possible with incredible computing power and digital bandwidth. It’s still early on in the adoption curve of things like ChatGPT, Dall-E (images included here were generated by AI - still a work in progress clearly), and all the other virtual brains out there that can do things like translate text, draft documents, generate images and video, and even function as chat therapists.

Once we can use non-human labor for basic “going through the motions” activities, humans may all become “managers” who can deploy, assemble in novel formations, and quality-check the work of various AI tools in order to achieve the same result that would require a team of people today.

Even jobs that today require physical exertion, like construction, firefighting, and parcel transportation, may begin to see a shift toward automation and robotics as those capabilities improve. Imagine a smart crane with the dexterity of 50 people that can 3D-print an entire building site using material inputs and only minimal human intervention? The Los Angeles Fire Department already uses a robotic tank to enter dangerous fire-fighting scenes and address hot-spots that firefighters can’t reach.

My hope is that as a globalized, AI-aided society, humans will return to humanities-based education, which has been on the decline in favor of things like STEM, and human-centric ways of measuring success and compensation, encouraging young people to dabble throughout their twenties and attend university for intensive study only when they’re ready.

AI could induce a new global renaissance of arts, entertainment, and emotion-driven creativity, things that only humans can make for other humans in novel and unexpected ways. Perhaps we’ll pay a premium for human-created outputs over computer-created ones. An entire industry will be dedicated to authenticating human creative work vs. iterative, repackaged content.

If so many things can be produced by computers, that leaves bigger, more existential issues like public health, poverty, and climate change for humans to tackle and collaborate upon. The age of AI may spell the death of “work” as we know it, but in its place introduce a new age of humanism, of cooperation, and of inspiration. We hope.

I have another article in the funnel with the working title Why doesn’t college happen at 30? because I don’t believe anyone is ready to “pick a lane” as a teenager. And why should they, now that computers can do most anything and the issues of our world are far more nuanced than a singular, discipline-specific college degree can address?

Interesting food for thought…